When reading transcriptions of medieval poetry, it’s easy to forget that they were often heard performed not only in verse, but also in song with musical accompaniment. One wonders which familiar melodies drove the meters of some of Marie de France’s lays or the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes. Marie de Champagne had Chrétien collect, collate, preserve, and embellish the Arthurian “chansons.” We cannot say for sure what prompted this commission. Were the stories naturally becoming popular again? Did Marie de Champagne have issue with the older versions of the tales? Was there need of translation from Latin and local languages? Was the arts culture going through – as ours is now – a reboot and remake period?

The subject of most of these tales was courtly love – they were written not only with the court woman in mind, but possibly even for the court woman. Was this a medieval form of real marriage counseling? What advice, suggestions, warnings were meant for the men to hear? What was meant for the women to hear? Was there an attempt to dispel or possibly even confirm relationship stereotypes? To what extent was the need or want for gender discussion part of this literary movement – or are we just assuming there was a deliberate social agenda at all? Was the court leading or directing the literary culture of its day, trying to keep up with it, or both? Was there an underlying social agenda behind the resurgence and popularizing of these tales? Was this a sort of a medieval MeToo movement or just entertainment?

(wish I could claim credit for this, but alas, I cannot. Go internet!)

So the next time I read Guigemar, or, let’s be honest – just about anything from the Lays of Marie de France [(c.1160-1215) – not to be confused with Marie de Champagne (1145-1198)] concerning a cloistered woman or a man and woman trying to work things out in their relationship I’ll wonder if there was a movement happening in England (where Marie de France was writing – Henry II’s court) and France (where Chrétien was writing) that is anything like what we are seeing today.

My son Morgan was flying a little Breton flag around the house recently

It happened again. The Tuesday before last was a cold winter day and as the bus started moving I heard a familiar rolling sound. It stopped between my feet: the pearl.

It’s become a little running joke with myself that whenever I see a lost fake pearl earring I think of the poem Pearl. It’s like it’s telling me it’s time to read Pearl again – one part serendipity, one part superstition.

Pearl is a medieval narrative poem thought to be written by the same unknown poet who wrote Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, and Cleanness. For this reason scholars often call this poet the “Pearl poet” or the “Gawain poet.” All four of the poems attributed to the Pearl poet are written in the same Northern dialect of Middle English, so you get some interesting Old Norse-sounding words like burne and tulk[1] which may at first seem foreign to Chaucer readers.

It’s a dream vision poem – a popular genre, particularly in 13th and 14th century England and France. Other examples of the dream vision poem are Roman de la Rose (a sort of medieval version of A Christmas Carol except with sex), Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess, and, of course, Piers Plowman.

Pearl deals with the grief we suffer from personal loss. The troubled narrator (described as a joyless jeweler) doesn’t say specifically what kind of loss he’s suffered – but it seems to point to the loss of a child. In any case, he’s very distraught. He compares his loss to a pearl, one that – literally, figuratively, or both – slipped from his hand[2] and rolled into a garden. The narrator has no hope of ever recovering his precious pearl in the physical world.

A “Pearl maiden” character appears and guides the narrator through the dream vision and “treats” him in a way very similar to that of Lady Philosophy from Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, however, the “treatment” administered by the Pearl maiden is that of Christian doctrine.

Aside from the rhyme scheme, the frequent use of alliterative verse, and stanza linking, an aspect of the poem I most appreciate is how the Pearl poet contrasts material objects and worldly desires with higher thoughts and places and uses imagery of cleanness, perfection, and roundness in every stanza in a natural way that never seems tedious or forced.

You’d think that after the 25th “spotless” or “round” we’d want to pull our hair out, but he – and I’m really sorry to do this to you – keeps the ball rolling – especially by using alliteration. Check out most especially 945-948 (just read it, even if you’re not used to Middle English – there’s a verse translation in Modern English below to help you get the gist of it):

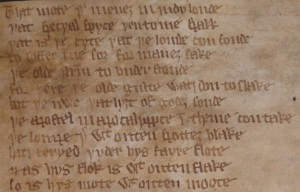

“The Lompe ther wythouten spottes blake / Has feryed thyder Hys fayre flote / And as Hys flok is wythouten flake / So is Hys mote wythouten moote.” It’s a beautiful poem and even if it doesn’t touch you spiritually in any way, its masterful constructed and flows like water. I leave you with a passage[3] from Pearl and a detail of the passage on its manuscript.

Here’s where the dreamer “sees” Jerusalem:

| “Thys moteles meyny thou cones of mele, Of thousandes thryght, so gret a route – A gret ceté, for ye arn fele, Yow byhod have wythouten doute. So cumly a pakke of joly juele Wer evel don schulde lyy theroute; And by thyse bonkes ther I con gele I se no bygyng nawhere aboute. I trowe alone ye lenge and loute To loke on the glory of thys gracious gote. If thou has other bygynges stoute, Now tech me to that myry mote.””That mote thou menes in Judy londe,” That specyal spyce then to me spakk. “That is the cyté that the Lombe con fonde To soffer inne sor for manes sake. The olde Jerusalem, to understonde, For there the olde gulte was don to slake. Bot the nwe that lyght, of Godes sonde, The apostel in Apocalyppce in theme con take. The Lompe ther wythouten spottes blake Has feryed thyder Hys fayre flote, And as Hys flok is wythouten flake, So is Hys mote wythouten moote.” (ll. 925-48)[4] |

“These holy virgins in radiant guise, By thousands thronged in processional – That city must be of uncommon size That keeps you together, one and all. It were not fit such jewels of price Should lie unsheltered by roof or wall, Yet where these river-banks arise I see no building large or small. Beside this stream celestial You linger alone, none else in sight; If you have another house or hall, Show me that dwelling wholly bright”That wholly blissful, that spice heaven-sent, Declared, “In Judea’s fair demesne The city lies, where the Lamb once went To suffer for man death’s anguish keen. The old Jerusalem by that is meant, For there the old guilt was canceled clean, But the new, in vision prescient, John saw sent down from God pristine. The spotless Lamb of gracious mien Has carried us all to that fair site, And as in his flock no fleck is seen, His hallowed halls are wholly bright.” (ll.925-48)[5] |

Here’s how the passage appears in the Manuscript Cotton Nero A.x. (art.3)[6]:

Lines 925-936 of Pearl from British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) folio 051 verso (image source)

Lines 937-948 of Pearl from British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) folio 052 recto (image source)

[1] Burne and tulk (man/knight) appear in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, ed. James Winny (Ontario, 1992).

[2] Reminds me of that last verse from the Cure song “A Letter to Elise” where the narrator says, “And every time I try to pick it up like falling sand / As fast as I pick it up it runs away through my clutching hands / But there’s nothing else I can really do / There’s nothing else I can really do at all.” The character in this song may need consolation from the Pearl poet after he posts his letter – unless, of course, he and Elise do this all the time.

[3] The Middle English version presented here has modernized spelling so you won’t find any thorns and yoghs. I’m looking forward to the forthcoming “diplomatic” transcription of Pearl edited by Murray McGillivray and Jenna Stook from The Cotton Nero A.x. Project (currently under scholarly review for publication). They are also working on a version of Cleanness (edited by Kenna L. Olsen) as well as Patience and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Murray McGillivray). For more information, check out: http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/publications.html

[4] Pearl in Middle English from Pearl, ed. Sarah Stanbury (Kalamazoo, 2001) available online

[5] Pearl in Modern English translation from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, and Pearl: verse translations, trans. Marie Borroff (New York, 2001).

[6] British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) is the only known manuscript of Pearl – it also contains Cleanness, Patience (or Job), and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. All four poems are thought to have been written by the same unknown poet.

In the 13th century Middle High German epic Das Nibelungenlied, a little name calling escalates into the death of our hero Sifried (Sigurd from the Volsung lengend). That almost happened in Better Call Saul a few weeks ago when two skateboarders unwittingly attempted to con Tuco’s grandmother.

When Tuco discovers this, he hogties the skateboarders and takes them out to the desert to execute them. Saul Goodman – who at this point in the story is still known as Jimmy McGill – provides legal defense for the skateboarders in an adhoc desert courtroom where the judge is a psychotic drug kingpin and the jury is comprised of the kingpin’s goons.

Though he seems willing to drop charges on the con, there is another offense that Tuco is not willing to forget: the two offenders called his grandmother a “Biznatch.” He seeks the death penalty for this one.

Smoothing Tuco over with lines like, “You’re tough – but you’re fair – You’re all about justice,” Saul eventually barters the punishment down from death to a broken leg. In the end, everyone feels the punishment fits the crime.

Jimmy McGill aka Saul Goodman (Bob Odenkirk) and Tuco (Raymond Cruz) negotiate in Better Call Saul. image copyright 2015 AMC, High Bridge Productions, Sony Pictures Television

Unfortunately for Sifried, Saul Goodman wasn’t around to counsel King Gunter when his wife Brunhild demanded justice after Sifried’s wife Krimhild called her a whore. Instead of Saul, Gunter had Hagen of Troneg who convinced his king that Sifried’s death was the only penalty that fit the crime.

It all started when Brunhild quarreled with Krimhild for daring to walk into church before her, “No maid in waiting is allowed to walk in front of a great king’s very own lady.”[1]

Krimhild doesn’t let this insult go without a comeback:

Krimhild quickly answered (easily as angry):

“You’d be better much off holding your tongue. Your shame

Is selling your beautiful body to acquire a lady’s name.

How can a whore transform herself a queen, when she’s been so shamed?[2]

(this odd spacing is intentional and is explained at the end of the post)

For those unfamiliar with the story, here’s why Krimhild said such a thing to Brunhild:

King Gunter isn’t the fittest man, but he set his eyes on the Icelandic queen Brunhild. To marry Brunhild you had to beat her in several physical challenges – boulder throwing, spear-throwing, stuff like that. If you lose, you die – but if you win, you get to marry Brunhild. There was no way King Gunter could defeat Brunhild in the games so, wearing a cloak of invisibility, Sifried helps Gunter defeat Brunhild. I wrote about this episode in a previous post.

Gunter gets to marry Brunhild, but as you can imagine she quickly realizes that he’s not the gladiator he seemed during the games. On their wedding night, Brunhild refuses sex and instead ties Gunter up and makes him spend the night hanging from the ceiling.

The next day when Sifried asks Gunter how his first night in the sack with Brunhild was, the humiliated king asks Sifried for his help. Sifried appears the second night – and with that cloak of invisibility – breaks Brunhild like a wild horse. Once she yields to him, he takes her belt and ring and lets King Gunter take over.

The belt was a magic belt of Nineveh silk. It was the source of Brunhild’s superhuman strength. And as for the red golden ring- could it be the cursed ring of Fafinir’s horde?

Brunhild looks at Krimhild and realizes she’s telling the truth:

“She’s wearing, now, the silken belt I lost, and my red-

Gold ring is on her finger. I’d wish I’d never been born,

My king, and live eternally sorry, unless you restore

My honor, free me from this utterly gross and ghastly slander.”[3]

King Gunter summons Sifried to tell his side of the story. Sifried tells Gunter that he never boasted to anyone that he had Brunhild’s body before the king had slept with her. Gunter frees Sifried of all charges. Just before leaving, Sifried adds:

“Men should make certain,” heroic Sifried went on,

“that women’s tongues are checked, kept from wagging loose.

You control your wife, and will try my best to make sure

Of mine. I’m thoroughly ashamed of such disgraceful behavior.”[5]

Seeing Brunhild unsatisfied with Gunter’s resolution, Hagen of Troneg convinces King Gunter that the only way to resolve this problem is to kill Sifried:

The king listened to evil Hagen, his trusted man

Burgundy’s faithless knights set to work

Worthy warriors preparing hidden betrayal and death

So just two women quarreled but many heroes would breathe their last.[6]

And so Sifried’s fate was decided just like that – he would be killed in a “hunting accident.” Justice would be served in hidden betrayal. Though King Gunter gave one verdict out in the open, the final verdict given in private was very different.

One wouldn’t expect the final judgment of a psychotic meth dealer on one of his enemies to be fairer than one decided on by a king with the help of his wise advisors, yet it is.

Both of the penalties these powerful men imposed were intended to protect the honor of a woman who was very dear to each of them. For Gunter, it was his wife Brunhild; for Tuco it was his grandmother. Their method, however, couldn’t be any more different.

After receiving their punishment of one broken leg each, the skateboarders are free to go. Tuco agreed to a penalty and stuck with it. Though he is an emotionally unstable gangster who might kill someone for much less, we are somehow confident that he will keep his word.

This is not the case for Sifried though – the king who publicly told him his charge was dropped will – minutes later – turn around and privately condemn him to death. Why is Tuco the character we can trust to be fair and just? It must have been the sleazy, yet strangely ethical lawyer – Sifried failed to call one.

——————————————————————————

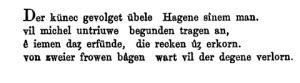

A note about the spacing in Burton Raffel’s English translation/rendering: The spacing is to preserve the half-lines of the quatrains. Raffel explains, “Each line is divided, visually as well as metrically, into two half-lines. The first seven half-lines of each quatrain (that is, the first three and a half lines) have three metrical feet; the last half-line usually, but not always has, has four feet. I have followed this pattern very closely.”[7] He also notes that the quatrains in Das Nibelungenlied are not always end-stopped. Using the quatrain above (Raffel’s 876 – the final quatrain of Adventure 14) let’s look at manuscript C of Nibelungenlied.

detail of Das Nibelungenlied quatrain 876 from manuscript C. image source

Notice the marks indicating the half-lines. In this quatrain they appear after übel, man, untriuwe, an, erfünde, erkorn, bâgen, and verlorn.

To see them a little easier, first look at the transcribed version below. An early 20th century editor[8] preserved the half-lines of the quatrain in his transcription.

The half-lines can look a little odd in Modern English translation in instances where the idea conveyed doesn’t seem to naturally elicit a pause. There’s a strange intoxicating rhythm to the poetry though. Try reading it aloud – but not just one quatrain, otherwise it won’t work – it should be an entire scene – or better yet, a full adventure. I can’t quite describe it – but reading it aloud like that somehow brings you deeper into the poem. Strange to say, but it’s enchanting. These half-lines are not exclusive to narrative poetry in Middle High German. They are used in Saxon poetry and Old Norse poetry as well. Popular examples are Beowulf and the Elder Edda.

[1] Raffel, p. 117, quatrain 838.

[2] Raffel, p.117, quatrain 839.

[3] Raffel, p. 119, quatrain 854.

[5] Raffel, p. 120-1, quatrain 862.

[6] Raffel, p. 122, quatrain 876.

[7] Raffel, p. 333.

[8] Das Niebelungenlied, ed. Friedrich Zarncke (Niemeyer, 1905) available online.

edit: 11/11/2016. Removed Spoiler alert for Season 1, ep.2 of Better Call Saul from the top of the post.

edit: 11/7/2019. Removed footnote 4 as it may be offensive to some in the audience when taken out of context.

I love reading medieval self-help books (or “mirrors for princes” – as scholars call them) like Secreta Secratorum and The Consolation of Philosophy. Both are great, but the one I spend the most time with is Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy. My interest in Chaucer led me to Boethius since Consolation is one of Chaucer’s favorite touchstones. Once you read Boethius (or Boece, as he is called in Middle English texts) you’ll forever see flashes of his guiding philosophy in Chaucer’s poetry. In any case, Boethius quickly became a friend in my own spiritual journey. My wife Jessica and I even used a passage from The Consolation of Philosophy in our wedding ceremony. And no, it wasn’t a “medieval-themed” wedding THANK YOU VERY MUCH!

I love reading medieval self-help books (or “mirrors for princes” – as scholars call them) like Secreta Secratorum and The Consolation of Philosophy. Both are great, but the one I spend the most time with is Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy. My interest in Chaucer led me to Boethius since Consolation is one of Chaucer’s favorite touchstones. Once you read Boethius (or Boece, as he is called in Middle English texts) you’ll forever see flashes of his guiding philosophy in Chaucer’s poetry. In any case, Boethius quickly became a friend in my own spiritual journey. My wife Jessica and I even used a passage from The Consolation of Philosophy in our wedding ceremony. And no, it wasn’t a “medieval-themed” wedding THANK YOU VERY MUCH!

Reading Boethius in modern English translation alone, however, does not satisfy the medievalist. We look to “the versions they used” and while we might not always find them, there are other versions that give us ideas of how Boethius was appreciated in the medieval world. Chaucer translated a version himself into English but he was not the first to do so. An Old English version[1] is attributed to Alfred the Great, the 9th century Saxon king of England. How involved Alfred actually was in its composition will likely never be known, but we know that he placed great value on the text and at least commissioned its production.

Reading Alfred the Great’s version, you’re instantly struck by its heroic language. The quick prologue Alfred provides smacks of the opening lines of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and Green Knight. In Alfred’s version Boethius is a Christian man who fights for justice to save his people from the evil tyrant Theodoric.

After the spirited prologue, however, the narrative becomes – more or less – the one we recognize from Consolation.

Something interesting about the Saxon version of Boethius attributed to Alfred the Great, though, is that the character Lady Philosophy is called Wisdom (and sometimes Reason). Her character is also masculine rather than feminine, but aside from that we are not given any other physical characteristics.

Boethius isn’t “visited” by Lady Philosophy in reality or dream vision in the Saxon version. It is as if the “Wisdom” and “Reason” dialogue with the “mind” occurs in the character’s head whereas in Consolation Lady Philosophy (also referred to as a physician) appears and “treats” Boethius.

Also, the “muses” Lady Philosophy chases away are simply referred to as “worldly pursuits” in the Saxon version as opposed to a greater pursuit: striving to know – but not being arrogant enough to think one can “possess entirely” – wisdom.

Consolation presents a philosophy that is somewhat universal, but the Saxon version manages to be even more universal in a way. It isn’t watered down to the extent of a message from Joel Olsteen, for example, but the concepts are presented in a disarming way that complements Christian thought and could help a medieval reader in much the same way a Joel Olsteen book would help someone today.

Comparing Boethius to Joel Olsteen may seem inappropriate to some medievalists, but I’ll bet Boethius was more accessible than Aquinas (or even Dante) among contemporary medieval readers. The method is also surprisingly similar to modern psychoanalysis and behavior change through self-awareness.

In addition to the text’s teaching and guiding philosophy that is meant to complement Christian thought, something makes the king who promoted the text seem revolutionary for his time. In Alfred’s version, the hero Boethius is a senator who feels his leader is not morally fit to govern his people so he seeks to remove him from power. A king who promotes this kind of hero is telling his subjects that rulers are to be held at the highest moral standard and are obligated to share wisdom and book-learning with their people. And if they don’t – any one of their subjects should remove them from positions of power. That sounds a lot more like democracy than feudalism!

[1] King Alfred’s Anglo Saxon Version of Boethius De Consolatione Philosophiae, trans. Samuel Fox (London, 1864) available online

14th century illustration from Golden Haggadah of Moses being found (image source)

In Exodus, the narrator uses only three verses[1] to take the baby Moses from being handed to a Hebrew wet nurse to becoming a young adult. The story moves very quickly. After Moses is saved from the river by Pharoah’s daughter, we fast-forward to him as a young adult just in time for the scene where he kills the Egyptian. This period of baby Moses’ life is given much more attention in a 14th century version from The Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament than it is in Exodus.

First there’s this whole scene about how Moses refused to drink milk from any woman but his own mother and then there’s this interesting scene where Moses as a small child is brought into the royal chamber to see Pharoah. Moses’ foster-grandfather is delighted to see the bouncing boy and like every proud relative wanting to put on a show of the little guy’s brightness and good manners, he puts his crown on the young lad’s head for a Kodak moment. But little Moses, instead of sitting on Pharoah’s lap adorably modeling the big crown on his tiny head, puts the crown beneath his feet and tramples it:

“Betwyx hys schankes he sett hym right

and lappyd hym to hym for grett lufe.

And for he was so worthy a wyght,

Hys pertenes he toght forto prove.

His crown of gold, full fayr and bryght,

that barne hed sett he above.

And sone was schewyd in ther syght

a wonder case forto controve:

That child full lyghtlt lete,

the crown kast he downe,

And fylyd yt with his fete

forto breke yt full bowne.”

(ll. 1549-1560)[2]

Pharaoh’s advisors are appalled by this blatant scene of Jewish insubordination. They warn Pharaoh of the danger of allowing the Hebrew boy to grow to a man and they scoff at Pharaoh’s allowing him to live so close to the royal family. Pharoah hears nothing of their nonsense though – Moses is a clever little boy but he cannot possibly understand the implication of his action in light of current Egyptian-Jewish political tensions much less the prophecy that a Hebrew man will end Pharoah’s rule. It’s just a cute scene and besides – kids do the darndest things! Another advisor – who the text describes as “a wys man of ther law” – chimes in to defend the little child suggesting they conduct an experiment to test his cleverness. Some hot coals are brought in and presented to the little boy and sure enough Moses tries to put them in his mouth. So there you have it, he’s only a cute little boy who doesn’t yet know to be careful around burning objects.

At this moment Pharoah’s daughter (called Tremouth in The Paraphrase) rushes into the scene and takes the poor child in her arms back to her chamber to comfort him. The narrator reminds us that God always comes to those in need for he who saves shall be saved:

“Loe how sone God hath socur sent;

That He wyll save, be savyd thei sall.”

Why this scene? Was it for comedic purpose? Was it an original embellishment?

Turns out, it’s adapted from a 1st century text by Josephus called Antiquities of the Jews. Here’s the scene as it appears in Antiquities:

Thermuthis therefore perceiving him to be so remarkable a child, adopted him for her son, having no child of her own. And when one time had carried Moses to her father, she showed him to him, and said she thought to make him her successor, if it should please God she should have no legitimate child of her own; and to him, “I have brought up a child who is of a divine form, and of a generous mind; and as I have received him from the bounty of the river, in , I thought proper to adopt him my son, and the heir of thy kingdom.” And she had said this, she put the infant into her father’s hands: so he took him, and hugged him to his breast; and on his daughter’s account, in a pleasant way, put his diadem upon his head; but Moses threw it down to the ground, and, in a puerile mood, he wreathed it round, and trod upon his feet, which seemed to bring along with evil presage concerning the kingdom of Egypt. But when the sacred scribe saw this, (he was the person who foretold that his nativity would the dominion of that kingdom low,) he made a violent attempt to kill him; and crying out in a frightful manner, he said, “This, O king! this child is he of whom God foretold, that if we kill him we shall be in no danger; he himself affords an attestation to the prediction of the same thing, by his trampling upon thy government, and treading upon thy diadem. Take him, therefore, out of the way, and deliver the Egyptians from the fear they are in about him; and deprive the Hebrews of the hope they have of being encouraged by him.” But Thermuthis prevented him, and snatched the child away. And the king was not hasty to slay him, God himself, whose providence protected Moses, inclining the king to spare him.[3]

Besides adding the bit about the hot coal test, the scene was not an embellishment at all by the Paraphrase poet. In fact, it’s a surprisingly accurate translation given his version was put into Middle English verse with a slightly comedic mood. Makes me wonder what other texts the Paraphrase poet used to prepare his version of the Old Testament.

[1] Exodus 2:8-10: Douay-Rheims: http://www.drbo.org/chapter/02002.htm ; KJV: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?version=KJV&search=Exodus%202

[2] References to Exodus from the Metrical Paraphrase are taken from The Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament, ed. Michael Livingston (Kalamazoo, 2011).

[3] Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, trans. William Whiston. Available online: http://www.biblestudytools.com/history/flavius-josephus/antiquities-jews/book-2/chapter-9.html

When I think violence in medieval French poetry, I think Chanson de Roland. After all, who can forget Roland impaling Aëlroth with his lance, hoisting him high up in the air, and then tossing the freshly dead foe a good spear’s length away? There are other medieval French tales with violence. There are violent deaths in Marie de France. For example, in her lai Equitan, two adulterers are boiled to death in baths of scalding water. Though the violence is gruesome, it is described in the way violence appears in fables or fairy tales and folk tales: direct and to the point. The poet or storyteller simply says, “They were burned alive in a bath of boiling water.” The descriptions typically lack the relish and gruesome detail found in other works of medieval poetry like Chanson de Roland. If someone were burned alive in a bath of boiling water in Chanson de Roland, the poet would likely go on about the burns, mingling their shrieks of pain with steam silently rising from the water.

Now, you also have violence in the French versions of Arthurian tales like the Arthurian Romances and Perceval by Chrétien de Troyes and the anonymous Mort de Roi Artu, but I’d previously found that the violence in these texts was reserved for tournaments and single-person combat scenes. The scenes can get quite bloody, but the wounds suffered are typically the type to heal after a poultice and a day or two of sitting out the hunt. In other words, justice is not usually served in these tales with a violent death. It’s more likely the offender would be sent to personally apologize to Queen Guinevere and then spend the rest of his life in her service as punishment for his rude behavior to women or something like that.

But after seeing his description of Erec in a rotten mood being ambushed by three robbers in the woods a few days ago, I realized I had been wrong about the 12th century poet Chrétien de Troyes. He deserves his own installment of Today’s Medieval Bloodfest. This one comes from Erec et Enide the first of his Arthurian Romances.[1]

Erec is King Arthur’s second favorite knight. He’s probably Arthur’s real first favorite knight, but we know what a fragile ego Gawain has in the French books. Gawain’s a pretty good guy in the English books, but in the French he can be a bit of a jerk. If I was one of the Knights of Round Table knowing I only got the job because I’m the king’s nephew I guess wouldn’t be a very secure fellow in the company of self-made heroes either. Anyway, back to Erec – he accompanies Queen Guinevere and her maiden on the hunt for the White Stag. Stuff happens and Erec is forced to separate from Guinievere and go on a quest. During this quest he defeats a rude knight in single-combat and sends him back to Queen Guinevere for further punishment for his wretched offense. Erec meets a maiden named Enide, he gives her the honor to hold a hawk that only the most beautiful woman in the land can do and then brings her back to King Arthur’s court where an even greater honor is bestowed upon her – publicly receiving a kiss from King Arthur – a ceremony associated with the White Stag hunt.

Erec marries Enide and they live happily ever after. Well, almost. Before Erec met Enide he was one of the greatest knights around, but since meeting Enide he’s stopped competing with other knights and instead spends all of his time adoring his lovely wife. Though he still gives his fellow knights money for gear and travel expenses, he’s basically dropped out of the tournament circuit entirely. Erec doesn’t seem to mind, but it starts bothering his wife. She hears the nasty things his friends say about him behind his back, how he’s lost his reputation as a knight and everything. These were the very friends her husband was personally helping rise in the ranks!

Now, one night Enide can’t hold it in anymore. She cries and says that Erec has suffered great misfortune. Only Erec isn’t asleep. He hears her and demands to know everything. He rises immediately, puts on his gear, mounts his horse and bids his wife prepare herself to leave with him at once. They leave together. It isn’t a pleasant ride though. Erec is pissed off and tells his wife not to say anything to him until he says so. After a while three robbers take notice of them and decide to raid them. Though there are three of them, they attack one by one. I love how Chrétien explains this:

“In those days it was the custom and practice that in an attack two knights should not join against one; thus is they too had assailed him, it would seem that they had acted treacherously.”[2]

The robbers were concerned about someone thinking they had acted treacherously. Imagine that! Were they polite robbers? Still, it’s interesting how in tales of chivalry, everyone – even villains – have some regard for humanity. This is why it is difficult to find scenes in them that are violent enough for Today’s Medieval Bloodfest. There simply isn’t the complete disregard for humanity in the texts that is required for violent characters. Bad guys, once caught, are taught a lesson and then proudly reform themselves.

Back to the story. Enide sees them, but Erec doesn’t seem to notice them. She tries to warn Erec. He doesn’t exactly hear her though, he just says something along the lines of, “I’ll forgive you for addressing me this once.” He turns just in time though to not be caught by complete surprise by the first robber:

When Erec hears him, he defies him. Both give spur and clash together, holding their lances at full extent. But he missed Erec, while Erec used him hard; for he knew well the right attack. He strikes him on the shield so fiercely that he cracks it from top to bottom. Nor is his hauberk any protection: Erec pierces and crushes it in the middle of his breast, and thrusts a foot and a half of his lance into his body. When he drew back, he pulled out the shaft. And the other fell to earth. He must needs die, for the blade had drunk his life’s blood.

Here is that passage in Old French and Modern French translation[3]:

| Quant Erec l’ot, si le desfie ;

Andui poignant, si s’entrevienent, Les lances esloingnies tient ; Mais cil a a Erec faille, Et Erec a lui malbailli, Qui bien le sot droit envahir. Sor l’escu fiert par tel hair, Que d’un chief en l’autre le fent, Ne li hauberz ne le desfent : En mi le piz le fause et ront, Et de sa lance li repont Pié et demi dedenz le cors. Au retraire a son cop estors, Et cil cheï ; morir l’estut, Car li glaives ou cors li but. |

Quand Erec l’entend, it le défie.

Ils se precipitant l’un à la rencontre de l’autre, tenant les lances à l’horizontale. Mais le brigand a manqué Erec, alors qu’Erec l’a mis en piteux état, car il a bien su adjuster son coup. Il le frappe sur l’écu avec une telle violence qu’il le fend de haut en bas. Il n’est pas advantage protégé par son haubert qu’Erec disloque et brise au milieu de la poitrine, avant de lui enforcer sa lance d’un pied et demi dand le corps. En retirant sa lance, il la fait pivoter et l’autre tombe : il lui fallu mourir, car la pointe de la lance lui but le sang du coeur. (Vv. 2856-2870) |

Next come the other two robbers:

Then one of the other two rushes forward, leaving his companion behind, and spurs toward Erec, threatening him. Erec firmly grasps his shield, and attacks him with a stout heart. The other holds his shield before his breast. Then they strike upon the emblazoned shields. The knight’s lance flies into two bits, while Erec drives a quarter of his lance’s length through the other’s breast. He will give him no more trouble. Erec unhorses and leaves him in a faint, while he spurs at an angle toward the third robber. When the latter saw him coming on he began to make his escape. He was afraid, and did not dare to face him; so he hastened to take refuge in the woods. But his flight is of small avail, for Erec follows him and cries aloud, “Vassal, vassal, turn about now, and prepare to defend yourself, so that I may not slay you in an act of flight. It is useless to try to escape.” But the fellow has no desire to turn about, and continues to flee with might and main. Following and overtaking him, Erec hits him squarely on his painted shield, and throws him over on the other side. To these three robbers he gives no further heed: one he has killed, another wounded, and of the third he got rid by throwing him from earth to steed. He took the horses of all three and tied them together by the bridles[4]. In colour they were not alike: the first was white as milk, the second black and not at all bad looking, while the third was dappled all over.

So it turns out Chrétien de Troyes can carry his own in poetic descriptions of gruesome violence. While Marie de France might have only used a line or two to say that Erec stabbed the robber in the heart with his lance, killing him with one blow, Chrétien uses 9 lines to describe Erec’s blow that could easily pass for a brutal passage in Chanson de Roland. Chrétien ends the violent passage by telling us that Erec’s lance drank the very blood that gave his attacker life straight from its source – his heart.

[1] Some say that he wrote an earlier Tristan but it is lost.

[2] References to Erec et Enide in Modern English translation are taken from Chrétien de Troyes: Arthurian Romances, Trans. W.W. Comfort (London, 1963).

[3] Erec et Enide in Old French and Modern French translation from Erec et Enide, ed., trans. Jean-Marie Fritz (Paris, 1992).

[4] I guess that’s the penalty for trying to steal from others – even if they are richer than you. Or, perhaps it’s what happens when you pick on a guy who is fighting with his spouse –he might not give you mercy and send you to be dealt with by the King. Instead, he might just harshly render justice right then and there – and take your horses too!

So you know Marco Polo the Venetian? The story goes Marco Polo told this French guy all about his travels while he was in prison in Genoa. The first manuscript of The Travels of Marco Polo is 13th century and was written in Old French. Anyway, one of the little stories[1] he heard was from his brothers Nicolas and Maffeo when they were in Jordan. They heard about these Christians who had a flame in their temple that was so popular people came from miles around to light their lamps with it because it was Holy light, etc. – sort of like a relic. When the Magi (or, the Three Kings) went to visit baby Jesus, they brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh. These gifts were to test the prophet. If the prophet chose the gold he was only an earthly king and if he chose the myrrh he was a physician – but if he chose the frankincense he was truly a prophet. Well, it turns out the baby Jesus accepted all three gifts and gave them a little box in return.

On their way home the Magi opened the little box to see what was inside. It was a little stone – meant to symbolize their faith in Christ – steadfast, like a rock, etc. Well, that symbolic meaning went straight over their heads and they thought it was a stupid gift so they threw the stone in a well. At that moment, a huge blast of fire came from the heavens, hitting the stone, and setting it alight. It has been burning ever since. So that’s why people come to visit the temple.

Now, I can’t tell whether this temple was a major pilgrimage spot in 13th century Jordan or if some rural village was just enjoying its fifteen minutes of fame while Nicolas and Maffeo Polo were passing through. It is interesting though, that in the Medieval World stories were written to embellish Biblical sources. A couple of interesting ones are the Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament and The Three Kings of Cologne. The latter is kind of like a “Further Adventures and exploits of the Three Kings.” It’s a text with a strong Christian message told in the style of a medieval travel narrative. The Three Kings’ characters are fleshed out in this text. We know their names, where they’re from, and what they do after visiting the baby Jesus besides not returning to King Herod and going home by another route – but more importantly, the text gives you an idea of how the author thought various Temples and newly formed sects responded to the news of the Christ’s birth.

Though the little box and fiery stone gift from baby Jesus is not mentioned in the The Three Kings of Cologne, the text mentions that their gifts were meant to test the baby Jesus.[2] The text does mention, however, another “relic” collected from the nativity, adding that cringe-worthy touch of anti-Jewish sentiment found in most Medieval Christian texts written for a popular audience.

After the Kings traveled around, relating their tale of having seen the Christ, Mary grew frightened that the Jews would come and get her, so she went underground (literally) into a dark cave and waited there until things calmed down a little:

“þer bygan to wex a grete fame of oure lady and of her childe and of þes .iij. kyngis alle aboute. wherfore oure lady for drede of þe Iwes fledde oute of þat litil hows þat crist was bore in, and went in to an oþir derke Cave vndir erþe: and þere sche abode with her childe til þe tyme of her Purificacioun.”[3]

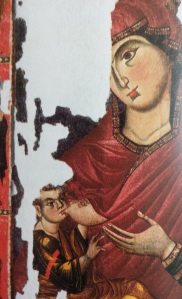

Madonna Suckling the Child, in Venetian vernacular known as the Madona de la late, panel, 13th-14th century. Venice, Museo di S. Marco. Image: Venice: Art & Architecture, Könemann.

While Mary was in that cave she sat on a stone and nursed the baby Jesus. Some of her breast milk sprayed on that stone. Sometime later, the cave was turned into a chapel and became a pilgrimage spot. It still had that stone and it still had milk too. If the stone was scraped with a knife, it would spray some of Mary’s breast milk. Just imagine going to a pilgrimage spot and hearing the guide say, “And Behold the everlasting milk still flows! For a small donation you can take a few drops!” That’s not the only mention of stones and the baby Jesus in Three Kings. More detail is given about the star they saw that signified the Christ was born. Its edges resembled that of a cornerstone.

So, according to The Three Kings of Cologne, after they described the star to people, it was pretty fashionable to put it on all the temples that had decided to follow Jesus. So I guess they did get the metaphor after all – you know, Jesus being like a stone at a strong building’s foundation.

[1] My telling of this tale is loosely adapted from Yule-Cordier’s edition of The Travels of Marco Polo.

[2] Makes me think of the Dalai Lama choosing his glasses!

[3] John of Hildeshesheim, The Three Kings of Cologne: an early English translation of the “Historia Trium Regum”, ed. C. Horstmann. available online