It happened again. The Tuesday before last was a cold winter day and as the bus started moving I heard a familiar rolling sound. It stopped between my feet: the pearl.

It’s become a little running joke with myself that whenever I see a lost fake pearl earring I think of the poem Pearl. It’s like it’s telling me it’s time to read Pearl again – one part serendipity, one part superstition.

Pearl is a medieval narrative poem thought to be written by the same unknown poet who wrote Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, and Cleanness. For this reason scholars often call this poet the “Pearl poet” or the “Gawain poet.” All four of the poems attributed to the Pearl poet are written in the same Northern dialect of Middle English, so you get some interesting Old Norse-sounding words like burne and tulk[1] which may at first seem foreign to Chaucer readers.

It’s a dream vision poem – a popular genre, particularly in 13th and 14th century England and France. Other examples of the dream vision poem are Roman de la Rose (a sort of medieval version of A Christmas Carol except with sex), Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess, and, of course, Piers Plowman.

Pearl deals with the grief we suffer from personal loss. The troubled narrator (described as a joyless jeweler) doesn’t say specifically what kind of loss he’s suffered – but it seems to point to the loss of a child. In any case, he’s very distraught. He compares his loss to a pearl, one that – literally, figuratively, or both – slipped from his hand[2] and rolled into a garden. The narrator has no hope of ever recovering his precious pearl in the physical world.

A “Pearl maiden” character appears and guides the narrator through the dream vision and “treats” him in a way very similar to that of Lady Philosophy from Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, however, the “treatment” administered by the Pearl maiden is that of Christian doctrine.

Aside from the rhyme scheme, the frequent use of alliterative verse, and stanza linking, an aspect of the poem I most appreciate is how the Pearl poet contrasts material objects and worldly desires with higher thoughts and places and uses imagery of cleanness, perfection, and roundness in every stanza in a natural way that never seems tedious or forced.

You’d think that after the 25th “spotless” or “round” we’d want to pull our hair out, but he – and I’m really sorry to do this to you – keeps the ball rolling – especially by using alliteration. Check out most especially 945-948 (just read it, even if you’re not used to Middle English – there’s a verse translation in Modern English below to help you get the gist of it):

“The Lompe ther wythouten spottes blake / Has feryed thyder Hys fayre flote / And as Hys flok is wythouten flake / So is Hys mote wythouten moote.” It’s a beautiful poem and even if it doesn’t touch you spiritually in any way, its masterful constructed and flows like water. I leave you with a passage[3] from Pearl and a detail of the passage on its manuscript.

Here’s where the dreamer “sees” Jerusalem:

| “Thys moteles meyny thou cones of mele, Of thousandes thryght, so gret a route – A gret ceté, for ye arn fele, Yow byhod have wythouten doute. So cumly a pakke of joly juele Wer evel don schulde lyy theroute; And by thyse bonkes ther I con gele I se no bygyng nawhere aboute. I trowe alone ye lenge and loute To loke on the glory of thys gracious gote. If thou has other bygynges stoute, Now tech me to that myry mote.””That mote thou menes in Judy londe,” That specyal spyce then to me spakk. “That is the cyté that the Lombe con fonde To soffer inne sor for manes sake. The olde Jerusalem, to understonde, For there the olde gulte was don to slake. Bot the nwe that lyght, of Godes sonde, The apostel in Apocalyppce in theme con take. The Lompe ther wythouten spottes blake Has feryed thyder Hys fayre flote, And as Hys flok is wythouten flake, So is Hys mote wythouten moote.” (ll. 925-48)[4] |

“These holy virgins in radiant guise, By thousands thronged in processional – That city must be of uncommon size That keeps you together, one and all. It were not fit such jewels of price Should lie unsheltered by roof or wall, Yet where these river-banks arise I see no building large or small. Beside this stream celestial You linger alone, none else in sight; If you have another house or hall, Show me that dwelling wholly bright”That wholly blissful, that spice heaven-sent, Declared, “In Judea’s fair demesne The city lies, where the Lamb once went To suffer for man death’s anguish keen. The old Jerusalem by that is meant, For there the old guilt was canceled clean, But the new, in vision prescient, John saw sent down from God pristine. The spotless Lamb of gracious mien Has carried us all to that fair site, And as in his flock no fleck is seen, His hallowed halls are wholly bright.” (ll.925-48)[5] |

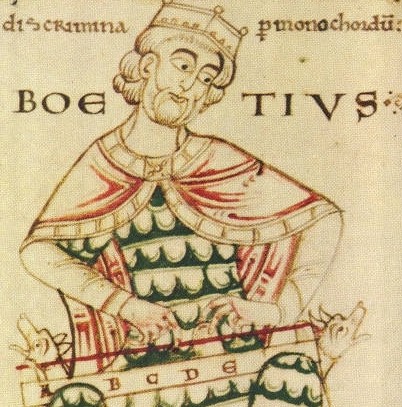

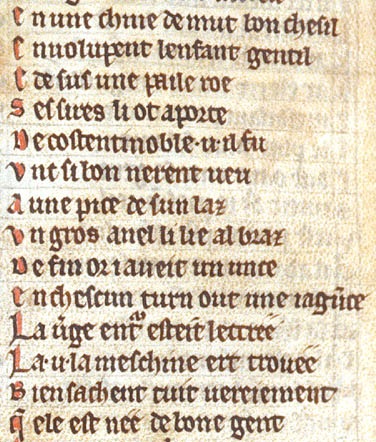

Here’s how the passage appears in the Manuscript Cotton Nero A.x. (art.3)[6]:

Lines 925-936 of Pearl from British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) folio 051 verso (image source)

Lines 937-948 of Pearl from British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) folio 052 recto (image source)

[1] Burne and tulk (man/knight) appear in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, ed. James Winny (Ontario, 1992).

[2] Reminds me of that last verse from the Cure song “A Letter to Elise” where the narrator says, “And every time I try to pick it up like falling sand / As fast as I pick it up it runs away through my clutching hands / But there’s nothing else I can really do / There’s nothing else I can really do at all.” The character in this song may need consolation from the Pearl poet after he posts his letter – unless, of course, he and Elise do this all the time.

[3] The Middle English version presented here has modernized spelling so you won’t find any thorns and yoghs. I’m looking forward to the forthcoming “diplomatic” transcription of Pearl edited by Murray McGillivray and Jenna Stook from The Cotton Nero A.x. Project (currently under scholarly review for publication). They are also working on a version of Cleanness (edited by Kenna L. Olsen) as well as Patience and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Murray McGillivray). For more information, check out: http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/publications.html

[4] Pearl in Middle English from Pearl, ed. Sarah Stanbury (Kalamazoo, 2001) available online

[5] Pearl in Modern English translation from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, and Pearl: verse translations, trans. Marie Borroff (New York, 2001).

[6] British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x. (art. 3) is the only known manuscript of Pearl – it also contains Cleanness, Patience (or Job), and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. All four poems are thought to have been written by the same unknown poet.