Sequitur pars quinta.

When King Alla returns to his castle he is surprised to see that his wife and child are nowhere to be found. He asks the constable where they are. The constable is confused and shows King Alla the letter he received with orders in his name:

“Lord, as ye commanded me

Up peyne of deeth, so I have done, certain.” (884-85)

With this, the messenger is tortured until he tells, “plat and pleyn, Fro nyght to nyght, in what place he had leyn” (886-887).

Chaucer’s Man of Law doesn’t tell us which form of torture King Alla used to get the messenger to talk, but the messenger may have been dunked in the ducking-stool. Pictured is Ollie Dee being dunked after being charged with burglary in Toyland (Babes in Toyland / March of the Wooden Soldiers) (image: copyright 1934 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer).

King Alla discovers the disturbing truth that his own mother forged the letters that called for Constance to be pushed out to sea in a boat without oars. He finds her guilty of treason and we can only guess that she is swiftly put to death, because all Chaucer’s Man of Law says about the matter is,“thus endeth olde Donegild, with mischance!”

Now, Constance, who is once again faring the sea in a rudderless vessel, finally reaches the safety of land. And just when you’d think she’d find repose, it turns out she’s landed just below “an hethen castel.” The steward of the castle comes down to see who has arrived and when he realizes it’s a woman, he tries to have her against her will right then and there. As baby Maurice cries, Constance struggles with the assailant until he is thrown overboard and drowns. The Virgin Mary somehow comes to Constance’s aid, “But blisful Marie heelp hire right anon” (920). We are not told precisely how the power of Mary is manifest through Constance except by Christian miracle. The Man of Law supports this argument with Old Testament Scripture by asking the audience how this weak woman had the strength to defend herself against this renegade:

“How may this wayke woman han this strengthe

Hire to defende again this renegat?” (932-33)

He reminds us that in the Bible, Goliath was a giant warrior, yet young David defeated him in battle. As if presenting evidence for a case in a court of law, his second piece of “evidence” is even stronger and more relevant because it deals specifically with a woman defeating a wicked and powerful man. He references Judith who slew the general Holefernes, ending the Assyrian occupation in her land.

Remember that the Man of Law did this earlier in the tale when he told the audience how Constance survived the wedding massacre in Syria and was delivered safely to the Northumbrian shore. The miracles that deliver Constance from heathen treachery are comparable to other well-known saint characters in the Christian canon such as Jonah who survived the whale, Mary the Egyptian who survived alone in the desert wilderness, and, of course, Christ who fed the many with five loaves of bread and two fish. By doing this, The Man of Law provides evidence to prove that miracles occur because of Christ’s divine intervention and that, more importantly, the ones he cites are no different in significance to the miracles that save his story’s heroine. In a sense, he’s defending the legitimacy of Constance’s sainthood, however, Constance’s sainthood isn’t exactly on trial in this story.

While the Man of Law’s references may be meant to demonstrate his bookishness and familiarity with “Christian” law, their inclusion may not only call for lay people to read Scripture, but assume that the layperson appreciates these stories as much as he does. His delivery of the “evidence” to support his argument is entertaining. They are presented in a tone that may be perfectly read on both serious and lighthearted levels, providing the perfect balance of “sentence” (moral insight) and “solace” (pleasure).[1]

Though the references are traditionally accepted Christian miracles, they also provide us an interesting glimpse into 14th century English religious worldview. The Man of Law’s evocation of miracles from the Christian tradition in this tale is very similar to what folklorists call “sympathetic magic.” The concept behind sympathetic magic is based on “like influences like” and the notion “that the image of Christ or [another saint] overcoming [an] affliction [helps] the afflicted person overcome it as well.”[2] By using the images of David defeating Goliath and Judith slaying Holofernes, the audience understands how Constance would have the power through sympathetic magic to overcome her assailant in the boat just as an image of Jonah surviving the whale would help her survive the sea in a rudderless boat.

So back in the water Constance goes, floating every which way, “dryvynge ay / Somtyme west, and sometime north and south / And somtyme est, ful many a wery day.” (948-49)

Leaving Constance in the water again with the protective images of Christian heroes, the narrator turns back to the Roman Emperor. Once The Emperor hears of the wedding massacre that occurred at the Sultan’s palace, he sends his senator with ships over to Syria to pay them vengeance for their evil acts. The Sultan’s palace is burned to the ground and everyone is slain. On their way back to Rome, the senator’s fleet runs into Constance. They don’t know that the woman with the child is the Emperor’s daughter and either does she, as she still suffers from amnesia. When they return to Rome she lives with the senator and his wife just like she lived with the constable and his wife in Northumberland. The senator’s wife is actually Constance’s aunt, but none of them recognize each other.

Back the story goes to King Alla who feels compelled to go to Rome and give the Emperor his allegiance and to request forgiveness for his wicked works. Off he goes to Rome where he receives a welcome fit for a Christian king.

King Alla traveling to Rome and being able to communicate with everyone there reminds me to return to the question from the first post on Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale about how medieval storytellers deal with language barriers. Remember how Chaucer’s Man of Law has Constance speak a “Latyn corrupt” to communicate with the characters in Northumberland? Though the story is set in the 6th century, Chaucer may have used the linguistic landscape of 14th century Western Europe. Susan E. Phillips points out in “Chaucer’s Language Lessons” that a colloquial Latin was used as a lingua franca among merchants in late medieval Europe and that Chaucer’s characters’ use of this language in his Man of Law’s Tale suggests that multilingualism was not limited to the aristocratic class and that his use of this colloquial Latin in the story shows some of the linguistic changes that were occurring in late 14th century England.[3] Morris Bishop, as well, noted that during the High Middle Ages as the new culture in Western Europe became more cosmopolitan, “its common language [was] the easy, unpretentious Latin of the time.”[4]

Phillips also reminds us that in the 14th century the vulgar or common Latin was becoming vernacular Italian.[5] It would make sense for members of the royal court to understand colloquial Latin/Italian for the purpose of negotiating trades with merchants. The Man of Law, for example, learned the tale of Constance from a merchant and he shares this with the audience before beginning the story:

Nere that a marchant, goon is many a yeere

Me taught a tale, which that ye shal here (132-33)

The Man of Law, however, does not restrict this ability to communicate in Latin to characters in direct contact with members of the royal court. As we recall when Constance, the Constable, and Hermengyld were walking along beach, they came upon the “blinde Britoun.” Up until this point in the story, all characters in contact with Constance had been either members of the court or characters whose profession or post required frequent interaction with members of the court. Chaucer’s Canterbury pilgrim characters (the “audience” of the tale within the tale) don’t need to suspend their disbelief to accept that even characters from outside of the court can communicate using this colloquial Latin because the “pilgrims and their characters pick up foreign languages from their professional and personal lives rather than through formal education.”[6]

Chaucer may have “picked up” bits of foreign languages in this way as well. Peter Ackroyd, in his Chaucer biography, points out that Chaucer’s childhood home in London was several hundred yards from an area by the riverside where a community of Genoese merchants lived.[7] Though Chaucer may have studied Latin grammar of Donatus formally, Ackroyd notes that “it has been suggested that Chaucer’s knowledge of Italian sprang from such early contacts” with the merchant colonies in London.[8] Chaucer shows us that the merchants spread their linguistic currency with the noble class, but he is also interested in the parts tradesmen and the common man play in developing national language.

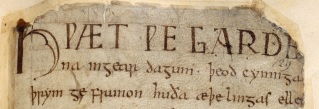

“The Man of Lawe – Of Dame Custance” – from added table of contents to a 15th century English manuscript of Canterbury Tales EL 26 C 09 commonly known as “Ellesmere Chaucer” (Huntington Library, San Marino) (image: http://www.scriptorium.columbia.edu)

Though most Chaucer tales blur the lines of contemporary storytelling styles, the Man of Law’s Tale is usually categorized as a secular saint’s life.[9] By choosing the style of a secular saint’s life, Chaucer could have employed xenoglossia both to deal with a possible language barrier issue and to demonstrate to the audience that Constance fits the description of a saint according to the literary styles of his day. Xenoglossia, the “sudden, miraculous ability to speak, understand, or be understood in… a foreign language previously unknown to the recipient… is described in a number of late medieval vitae and visionary texts.”[10] If Chaucer used xenoglossia to have Constance communicate with characters from other countries, he did it in a subtle manner because he doesn’t point it out. He could have said, “Lo and behold, by some great miracle, our Saint Constance could be understood!” Instead, he says something along of the lines of, “she spoke using a bit of pidgin Latin, but nevertheless, she was understood.” Christine Cooper argues that Chaucer puts Constance is an ambiguous xenoglossic situation[11].

If Chaucer used xenglossia in Man of Law’s Tale, it was likely to make his opinion on the position of the Latin language in 14th century English society ambiguous to protect him from making a divisive political statement. Chaucer mentions the Lollard movement[12] several times in the Canterbury Tales. If Chaucer is using language to provide commentary on either the common Englishman’s proficiency in Latin, the degree to which Latin is a common tongue among all Christian nations, or, if it isn’t whether or not Scripture should be translated into the emerging common tongue of England, English, then he is doing so with great subtlety and ambiguity. If the use of Latin in the story provides us Chaucer’s position on the state of the Catholic church’s role in England, he recapitulates at the end of the story with the most popular reference to Lollardy in the Canterbury Tales. Right after the tale ends, Jankin the Parson admonishes the Host for profanity in his exclamatory use of “Goddes bones” to which the Host replies, “O Jankin, be ye there? / I smelle a Lollere in the wynd.” (1172-73). The Host is the forum moderator of the Canterbury Tales, if you will, and his response to the Parson taking offense to his language suggests that Lollards can be staunch conservatives, and not necessarily liberators for the liberally leaning Englishman who feels persecuted in some way by Catholic Rome. Perhaps Chaucer’s joke about “those crazy conservative Lollards” was inserted as a way of protecting himself from making a statement about a saint coming to town and speaking a language that everyone understood. How shall we take the humor of that outburst?

Illustration of the Man of Law from the beginning of the Man of Law’s Tale in the “Ellesmere Chaucer” (Huntington Library, San Marino) (image: http://www.scriptorium.columbia.edu)

Now, something important to consider is when Chaucer was writing. “Latin is the dominant language in literature surviving from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries”[13] and Chaucer wrote during the end of the 14th century. By linguistic landscape, I’m not suggesting that everyone in 14th century England was conversationally proficient in Latin. I mean that the political and cultural landscape of the story has a 14th century flavor to it and the way language is used is part of the dynamics of the setting. Chaucer changes the political geography in his telling of Trevet’s story. Chaucer “makes the Imperial family Roman, whereas Trevet began his account by describing them specifically as Byzantine (“Capadoce”) – Tiberius Constanitus.”[14]

To be historically accurate, Rome was under Byzantine rule during the 6th century, yet, Chaucer uses 14th century geography. Taking a story that occurred in the past and putting it in a modern and contemporary setting was common practice in medieval literature. The geography isn’t the only detail, it’s also the culture, the language. Chaucer points out that Latin is being spoken, yet the Scripture that appears in the story is written in a local language. Chaucer is very specific that it is not a Latin Scripture but a version in the Welsh language – “A Britoun book, written with Evanguiles” (666) – which suddenly looks like the Welsh biblical translation cited in the Prologue of the Wycliffe Bible.” (124)[15] Could this be a way of Chaucer implying that Scripture should be translated into English – the emerging common language of 14th century England?

There is also a proto-Protestant tone to the story. The Man of Law, though not a church official is, in a sense, delivering a sermon. In fact, the entire Canterbury Tales shows a cross-section of 14th century English society demonstrating diverse Christian faith as one collaborative movement, warts and all. Is Chaucer calling for political religious reforms in 14th century England? Chaucer suggests that a land can become Christian on its own terms by retaining its own language, because throughout the subsequent process of Christianization, Constance’s offer of the true faith does not require the imposition of the Latin language upon the newly converted English.[16] Northumberland in the Man of Law’s Tale is an “early English kingdom [that] manages to become Christian while remaining – in Chaucer’s account – resolutely independent as an English homeland free of any foreign military, political, or linguistic domination.”[17]

Constance converts England to Christianity using a back to basics evangelical style that smacks of Jesus “prechynge the gospel of the kingdom” in Judea.[18] Both Constance and Jesus have Church authority in their respective stories by virtue of their lineage: Jesus from Abraham and King David and Constance from her father, the Roman Emperor. As Jesus comes “not to vndo the lawe, but to fulfille”[19], Constance brings Christianity to Northumberland “without submission to the authority of Rome and imposition of the Latin language.”[20] This idea of the diffusion of Christianity without clerical control was not a new idea in England at the time Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale was written.

The English crown along with some radicals like John Wycliffe didn’t see eye to eye with the Pope on the issue of taxation and there was a growing sentiment in England that The Bible should be taught in the vernacular. A proto-Protestant movement called Lollardy was so popular in England at the time that “you might hardly see two people in the street, but one of them would be a follower of Wyclif.”[21] Let’s not forget that Chaucer’s Man of Law’s tale was written and probably first performed in England during the reign of Richard II. He was “the first king since the Norman Conquest of wholly English parentage” and “the language generally spoken at Richard’s court was English.”[22] It was also a “breakthrough in the writing of English”[23] that saw the translation into the English vernacular of “highly learned argumentative Latin material”[24] and the sudden flourishing of national literature in the English vernacular. If “highly argumentative Latin material” was being translated into English, why couldn’t the Latin Vulgate Bible be translated as well? More importantly, if Latin was so widely spoken in England in Chaucer’s time as the story implies, why would translating The Bible into English make a difference anyway? Though the setting is 6th century England, Chaucer wants his audience to compare this fantasy revisionist story of England’s conversion to Christianity with the moral and political issues of their own 14th century contemporary society.

Well, there is more to the tale of Constance, “But of my tale make an ende I shal / The day goth faste, I wol no lenger lette” (1116-17)[25]. So let me summarize: Alla sees young Maurice as a page in the Roman Emperor’s court and is instantly reminded of Constance. He asks the Senator who the child is and the Senator tells him how he found him and his mother alone in a small boat in the middle of the sea. King Alla visits the Senator at his house and is reunited with Constance. King Alla and Constance return to Northumberland to rule King Alla’s land. Maurice later becomes the Roman Emperor. After King Alla dies, Constance returns to Rome. More details and a better telling in the old Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale, you’ll find because “I bere it noght in mynde.” (11127)

Heere endeth the tale of the Man of Lawe tolde by the weye.

[2] Kathleen Stokker. Foreword. The Black Books of Elverum (Lakeville: Galde, 2010), xiv.

[3] Susan E. Phillips, “Chaucer’s Language Lessons,” The Chaucer Review 46.1&2 (2011): 52,59.

[4] Morris Bishop, The Middle Ages (Boston, 1987), 257.

[5] “Chaucer’s Language Lessons,” 58.

[6] “Chaucer’s Language Lessons,” 40.

[7] Peter Ackroyd, Chaucer (New York, 2005), 4.

[8] Ackroyd, Chaucer, 15.

[10] “Translating Custance.”

[13] Brian Stone, Medieval English Verse (Harmondsworth, 1964), 13.

[14] John M. Bowers, “Colonialsim, Latinity, and Resistance,” in Fein and Raybin, eds., Chaucer: Contemporary Approaches 46 (University Park, 2011), 126.

[15] “Colonialism, Latinity, and Resistance,” 124.

[16] “Colonialism, Latinity, and Resistance,” 124.

[17] “Colonialism, Latinity, and Resistance,” 127.

[18] John Wycliffe. Matthew 4:23 in Forhsall and Madden, eds. The New Testament in English According to the version by John Wycliffe, about 1380, and revised by John Purvey about 1388. (London: Oxford, 1879).

[19] John Wycliffe, trans. Matthew 4:18.

[20] “Colonialism, Latinity, and Resistance,” 122.

[21] Terry Jones, Who Murdered Chaucer? (New York, 2004), 67.

[22] Who Murdered Chaucer?, 36.

[23] Who Murdered Chaucer?, 45.

[24] Who Murdered Chaucer?, 86.